Karl Robert Lindquist was born on May 7, 1925 in Nantucket, Nantucket County, Massachusetts.

Drafted by the Army at age 18 from a New England prep school before he graduated, Pfc. Karl Lindquist served in the infantry as first scout and later as a Medic. At 19 he was the youngest, most decorated G.I. in the 2nd Battalion-104th Infantry Regiment, with a Bronze and Silver star. The war in Europe ends on May 7, 1945 in Pilsen, Czechoslovakia. Pfc. Lindquist is there and it is his 20th birthday. He is one of five remaining members of the original 180 who landed together in France.

It was 1944, and Lindquist had just turned 18 when the Nantucket Draft Board gave orders for him and two other young Nantucket men to report for U.S. Army Infantry duty in Boston. The town didn’t announce their departure; there was no send-off party. The three young men quietly left their peaceful island hometown, not knowing if they would ever return.

Lindquist landed in France with a company of 180, and their daily lives were quickly turned upside down. "Days were spent in the field. Then we’d sleep in foxholes which we had dug, or were left by the Germans if they were retreating," says Lindquist. "In the morning, someone came around and woke us up. Breakfast of hot coffee was brought to us. Then we were assembled, and told what we were going to do that day. We carried our own rations. It’s funny because you don’t really think a lot about eating there. Your rations seem small, but after a week, you can hardly finish your meal. Your stomach must shrink."

The sustenance, usually just coffee and bread, was nothing to write home about. But not many soldiers wrote home anyway. "There wasn’t much opportunity to write," Lindquist says. "The guys who had young brides did more writing than anyone. I’d get a letter from my parents every once in a while, but I didn’t do much writing. I was too tired most of the time."

It’s no wonder Lindquist was so tired by nightfall; he spent his days as a scout. He would venture into the field alone, staying as low as possible, until he reached the nearest town to see what resources they had. Lindquist relayed an especially spine-chilling tale to M.A. Humphreys of the GI Generation Project. Lindquist had just scouted out a town full of tanks, and was heading back to camp. "A tank came out of the town," he recounts, "And cut across in front of me. I knew he hadn’t seen me because I saw the side of him. And he couldn’t see out the sides. So I hit the ground. And he sort of turned and he was right there next to me. When I looked up, I was lying flat. There were some others of them [also on the tank]. His gun was right over my head. And I’m like, 'What am I going to do now?' My inner voice said, 'Nothing. You just lie there. Pretend you’re dead. You’re dead if you move, so just stay there like that.' " The tank passed, bringing a wave of relief through the young man’s unharmed body.

Evening didn’t bring much relief from the stresses of the day. "At night, you’re usually with your foxhole mate, unless he’s been killed," says Lindquist. "Sometimes when you’re lying there, you think of funny little things to say to each other. By the end of the day, some fellows liked to sit around and talk. Mine and I liked to just go back to our foxhole. Usually we were just so tired that we went to sleep right then and there. The foxholes were 2.5 feet wide, 6 feet long, and 1.5 feet deep. It’s like a box that you’d lower a casket into. You set out your blanket roll, and one of you faces one way, the other faces the other. Sometimes, halfway through the night, one of you rolls over. You don’t talk about it; you just roll over so you’re not facing the other person. When it rained, we got wet. There was no relief from that. Then in the morning, you rolled up your bed roll and took it with you, unless you were dug into a place where you didn’t move from for days or weeks, like the Battle of the Bulge. Then you could use trees to cover yourself up so if there were any explosions overhead, the shrapnel wouldn’t come down and get you."

As you might imagine, there’s not much fun to be had at war. Lindquist says, "I recall no attempts at recreation hardly ever. We didn’t have the energy to kick a ball around. Not that we had a ball. The guys just sat around and talked to each other."

"It’s been 70 years. I feel a little awkward talking about it now. The guys who just got back two years ago probably have a lot more to say than I do. I don’t enjoy looking back on it. I don’t review the memories in my head as much as possible.” But on Memorial Day, Lindquist thinks of his fallen brothers. "To me, Memorial Day just means memories, of course. Memories of people, of what happened. I think about the whole chance of it, mathematically, of coming through and not being wounded or killed." Lindquist thinks back on a time he tried to talk a fellow soldier out of moving during an attack. The young man didn’t listen and was killed. Lindquist’s anguish over the boy’s death seems as fresh today as it was in 1944. "Everybody has to make their own decisions over there. And once you’ve been there, you know enough what not to do. I learned that when the shells start coming in, you don’t try to look for a safer place because no place is safe. You just keep a low profile, and maybe you’ll live through it, maybe you won’t. Guys will try to [cross the line of fire] and find safer place, and they get killed crossing. At one point, I realized, 'The longer I’m here, the longer I’ll last.' "

Of the original 180 who landed in France with Lindquist, only five survived. Lindquist’s message to Americans is this: “Be happy that you didn’t have to go through whole process of being there at war and having to save the world from being dominated by the Nazis. And remember how many people, how many lives, how many bad experiences it took to rescue our world from the Nazis."

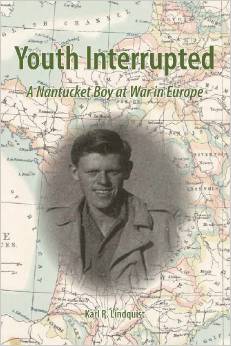

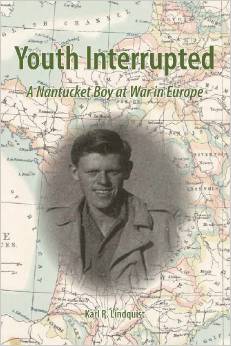

Karl Lindquist recounts his experiences in Youth Interrupted: A Nantucket Boy at War in Europe.

|

|

Pfc. Karl Lindquist at age 18 |

Pfc. Karl Lindquist as Medic at age 19 |